BLADENSBURG, Md.—The stomach-turning stench of old trash pulled from the Anacostia River didn’t deter volunteers from digging in Saturday morning.

Not with knives and forks, mind you, but gloved hands.

Eleven hardy high-schoolers and adults had answered a June plea from the Anacostia Watershed Society (AWS) to sort, weigh and count a sampling of the flotsam and jetsam collected in a trash trap in Northeast D.C. that the nonprofit monitors.

Why bother with such a tedious task? Concrete evidence helps the environmental organization plots its next advocacy moves.

By tracing the source of particular garbage streams, the society can collaborate with local government partners to put the squeeze on the sources of litter. For instance, legislation targeting plastic grocery bags and plastic foam have already curbed both of those once-common river pollutants.

Before Masaya Maeda emptied the first of 12 full, clear trash bags onto the asphalt driveway leading to the historic Bostwick House, the AWS water quality specialist explained how volunteers would use five-gallon buckets to divide the contents into 13 separate categories.

The cheerful leader kept the mood light by explaining that his boss tells him his first name is pronounced like Messiah, with the accent on the first syllable instead of the second.

“This is daunting,” Maeda said, calming those nervous about the classification system. “As we sort, we will become familiar with the categories.”

Indeed. It was simple to separate glass bottles, aluminum cans, tires, treated lumber, “large items” and “other non-plastics.”

Plastics—the bane of any conservationist, never mind the fish, birds and turtles—were a bit trickier. Bottles (by far the most ubiquitous), grocery bags and recreational balls were

simple to distinguish. Food wrappers, Styrofoam food containers, “other” Styrofoam and “other” plastics required a discerning eye.

By the way, cigarette butts go in the “other” bucket because they contain, surprise, plastic. Yes, it’s everywhere.

One caveat from Maeda: “Empty any water bottles with liquid so it doesn’t throw off total weight measurements. But do not open the ones with yellow liquid. It is urine. Set those aside.” Duly noted.

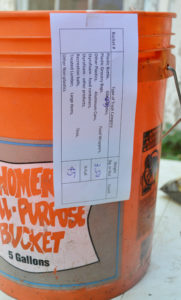

As the buckets filled, Maeda hung each one from a portable scale, recording its contents and weight on a chart he taped to its side.

Then, the counting began. Each item in each bucket had to be hand-tallied and returned to one of the soiled trash bags.

Bottles, cans and balls were a cinch. All of those food wrappers, lighters, drinking straws, tobacco pouches, wine corks and bits and bobs of Styrofoam and cellophane? Ugh! Not so much.

While the sorters could engage in light chatter, a hush fell over the counting area adjacent to the Bostwick barn. Who wanted to lose track and have to start over?

After the last plastic bottle cap was disposed of, Maeda gathered the volunteers for a few parting thoughts.

First, the trash sorted on June 25 came from a trap positioned near River Terrace, across the river from Kingman Island and RFK Stadium.

While traps are a giant advance for garbage collection along water bodies, the boom design of the River Terrace model captures only what floats—roughly 30% of the tons and tons of rubbish thrown, dumped or washed into the long-neglected Anacostia annually. (Maeda knows this because of painstaking probes organizing trash into 47 categories.)

Sadly, the rest, a whopping 70%, either sinks to the river bottom forever or becomes part of the endless, waterlogged trail of trash tumbling to the salt water of the Chesapeake Bay.

Thirteen major tributaries feed into the 8.5-mile Anacostia. AWS began experimenting with traps in 2009. In addition to the one at River Terrace, it maintains the Nash Run trap at the entrance to Kenilworth Marsh. This “screen” trap is more effective at catching a full panoply of trash, whether it floats or not.

As well, it coordinates with the Earth Conservation Corps to monitor at Diamond Teague, where the Anacostia flows into its more famous cousin, the Potomac.

Maeda didn’t immediately calculate the volume and weight from the dozen bags sorted data on that Saturday. Eventually, those figures will be added to the nonprofit’s carefully monitored running totals.

That valuable content isn’t just another pretty spreadsheet. It’s the proof AWS and its collaborators will draw on to peck away at convincing Washington, D.C. and Maryland to pass “bottle bills.”

AWS views the deposit/redemption law as crucial to eliminating the main sources of trash clogging the river the two jurisdictions share. Plastic bottles are by far the bulk of such litter, but the law also would apply to glass bottles and aluminum cans.

Despite, vociferous pushback from the beverage industry, 10 states have embraced such legislation.

If passed, a “bottle law” would piggyback on legislation that charges shoppers in D.C. and Montgomery County, Md., a nickel fee for each plastic grocery bag. As well, in 2016, those two jurisdictions joined Prince George’s County in Maryland in prohibiting plastic foam food and beverage containers.

A bottle bill is worth the uphill climb, Maeda concluded, the evidence mounded around him.

A light breeze, relatively low humidity and the can-do spirit of the volunteers meant the June 25 trash-sorting challenge, scheduled to last three hours, wrapped up 30 minutes early.

That was four days before the Anacostia Watershed Society issued the Anacostia an overall failing grade in its annual State of the River Report Card for 2022. AWS, intent on creating a fishable and swimmable river by 2025, has issued report cards since 2017.

This year’s score for trash reduction—one of eight diverse measurements categories—was a dismal “D,” at 63%. Much of that low grade is because stormwater runoff is the fastest-growing source of pollution in the Chesapeake Bay. Rain sweeps litter, toxics and sediment into the river.

Although AWS referred to the overall “F”—the second in five years—as a setback, the report compilers emphasized that long-term trends over three decades point to slow and steady improvements in water quality and ecosystem health.

As trash-sorting challenge volunteers drifted back to their parked vehicles, they passed the pile of bags containing that morning’s work—all deemed too dirty to recycle and thus headed for the landfill.

What were the weirdest items within? One baby shoe and a parking ticket.

The respective owners might be missing the former, but likely not the latter.