Everybody is likely aware that timber from trees is what’s ground into the fibrous pulp that is processed into all sorts of paper, from newsprint to book pages.

But what about adding words and images to that paper. How many people know that trees—specifically certain species of oaks in the genus Quercus—once provided the key ingredient for a long-lasting ink? The deep blue-black ink was prized by geniuses, artists, composers, authors and U.S. presidents who were drawing and writing masterpieces centuries before the ballpoint pen began dominating the marketplace in the 1950s and 1960s.

It’s called iron gall ink. Researchers can’t pin its “invention” on one particular person, however, in medieval times it was clearly somebody or somebodies with a keen eye for the natural world. They knew oak trees were rich with tannins, secondary compounds that not only inhibit fungal and bacterial growth but also deter insects and herbivores.

Despite those defensive attributes, at least one type of insect, commonly referred to as gall wasps, have figured out how to live their entire life cycle on and around oak trees.

In spring, the tiny adult wasps lay eggs on the underside of a leaf, on the acorn bud or the leaf bud. Feeding of the hatched larvae secretes chemicals that “irritate” the tree, altering the tree’s physiology/plant tissue. The tree defends itself by repairing the damaged site with protective growth.

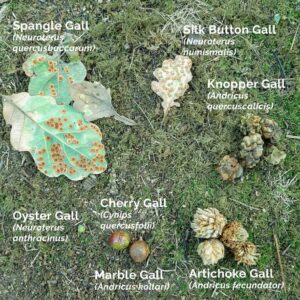

To be clear, there are thousands of types of galls that can grow on all types of trees and also can be caused by insects other than wasps, including mites, fungi, bacteria and viruses.

On oaks, the resulting gall is a round, tumor-like swelling that the parasites rely on for food and shelter. Cherry galls and marble galls are two common types of galls found on oak trees.

Briefly, cherry galls form on a leaf’s underside. Each gall contains a single larva of the Cynips quercusfolii species of wasp. These galls, which, fittingly, turn pink in early summer, remain in place until the leaves fall from the tree in autumn. The wasps that emerge from the leaf litter during winter will lay eggs on the tree bark.

Relatedly, marble galls form on oak twigs because the gall wasp, Andricus kollari, lays its eggs in the leaf bud in spring. The female wasp emerges in late summer or early fall, leaving a clear emergence hole in the brown gall. Usually, the vacant galls remain on the twig through winter.

In addition, oak apple galls are a mutation caused by a gall wasp, Biorhiza pallida, that lays its eggs on oak leaf buds. The gall, which is actually a deformed leaf, contains many larvae.

Now, about that ink. Observers of the outdoors had known for eons that some sort of substance in oak leaves turned puddles and streams brown. That substance is tannin. It’s plentiful in galls because it’s a tree’s attempt to keep the wasps as bay. Evidently, enterprising individuals figured that if that substance could darken water, why couldn’t it do the same for paper?

After all, the name tannin had been given to the plant extracts used to turn raw animal skin into leather during what came to be called the tanning process—a procedure birthed at the beginnings of civilization. In fact, the origin of the word tan is from an old English word meaning oak bark.

Angiosperms, gymnosperms, ferns and other higher plants produce tannins. Bark from a variety of species of oak, chestnut, black locust, pine and spruce continue to be vital sources of commercial tannins used today.

In medieval times, they realized they could harvest tannin from the empty galls, extract tannic acid, and stir that together with other substances to create ink with a desired velvety tone.

Historical recipes* for iron gall ink abound. The ingredients were inexpensive and readily available. In addition to tannin/tannic acid, the other three crucial ingredients are iron sulfate, gum Arabic and water.

Iron sulfate, also called vitriol, was obtained in a number of ways from mine sites. Gum Arabic is a pale yellow to deep golden orange vegetable gum from a tree native to Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria, the acacia. It served to modify the flow of ink from the writing instrument and bind the ink at the paper’s surface, thus producing more brilliant color.

Preparation usually called for boiling crushed or ground galls in rain water, wine or beer because those liquids produced fewer impurities. Often, the galls were allowed to ferment in water in a warm place for 10 days or so to maximize tannic acid extraction.

The filtered tannic acid was then mixed with the vitriol and gum Arabic. Other enhancements could modify the ink’s characteristics. For instance, indigo could enhance its visibility; adding pomegranate rind, walnut husks and various tree barks could provide extra tannin; sugar honey could create a more brilliant and slow-drying ink; vinegar, cloves and varying salts could slow mold growth; and brandy protected against freezing.

Two distinct advantages iron gall ink had over its common predecessor—carbon ink, which was made by burning oil, resin or tar to create soot—are portability and not clogging the writing tool. Conveniently, combining the dry ingredients made it transportable, as water could be added when it reached its destination.

The easily-made indelible ink was popular with anybody wielding a quill, reed pen or brush.

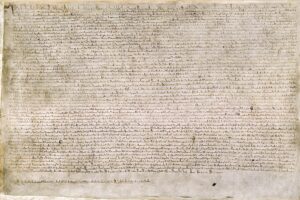

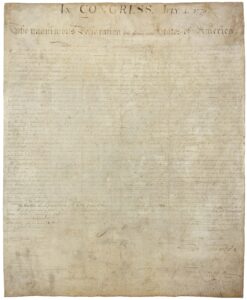

For instance, it was used in 1215 to write Magna Carta, the document that limited King John’s power in England. Across the Atlantic centuries later, it inked two other seminal documents, the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

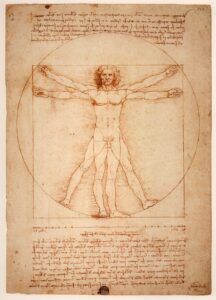

It’s found in Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks, Vincent van Gogh’s canvases, Johann Sebastian Bach’s musical scores and Jane Austen’s novels. It was the ink of choice for letters, maps and more mundane legal papers such as wills, logs and real estate transactions.

While iron gall ink was used as early as the fifth century, researchers agree it became the primary ink by the end of the late Middle Ages, roughly the 1400s.

It was used well into the 20th century, before giving way to synthetic dyes. Interestingly, it was the required ink for Germany’s official documents until 1974.

Entrepreneurs still experiment with it. For instance, one recent participant in an online forum, The Fountain Pen Network, wrote how excited she was to try out the iron gall ink recipe that English author Jane Austen used in the early 1800s to write masterpieces such as “Pride and Prejudice.”

Today’s oil-based ballpoint pen ink, usually encased in a plastic tube is quite dull by comparison. That ink is a blend of dyes, pigments, solvents, resins and other ingredients. Dyes and pigments give the ink color, liquid solvents dissolve the dyes and suspend the pigments, and resins bind the ink to paper. These days, resins are synthetically produced. However, some pigments come from bits of colored minerals, stones or metals and some solvents are plant-based substances such as rosin, linseed and rosewood oils.

And, I’d be remiss if I didn’t circle back to the pulpwood mentioned at the beginning because wasps, albeit a different species, are involved. Papermaking from plants began millennia ago with Egyptians turning to papyrus reeds and the Chinese combining bamboo, mulberry bark, silk and hemp.

Later on, the Europeans recycled linen, hemp and cotton rags—all plant-based—into paper. But a new source was needed when a shortage of textiles plagued the region. French entomologist René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur was tasked with finding a solution in 1719. The bug specialist who earlier had investigated the viability of spiders as a source for silk—suggested humans pay attention to the layered paper nests that wasps construct from gnawed wood.

By 1765, Jacob Christian Schäffer had acted on that advice by experimenting with the nests of wasps to fabricate paper. His durable result was proof that humans could make paper from trees.

After multiple failed attempts, machines were eventually built that could mimic what comes naturally to wasps—extracting fibers and processing paper from wood pulp. And, for good or for bad, industrial papermakers still turn to the trees.

NOTE: I wrote this paper for the Horticulture 100: Introduction to Plant Sciences course I took in fall 2024 at Montgomery College in Maryland. Our assignment was to do a presentation on plants and I figured this topic was an excellent fit for an ink-stained wretch.

* Recipe “to make inke to write upon paper” from A Booke of Secrets published by Edward White in London in 1596:

Take halfe a pint of water, a pint wanting a quarter of wine, and as much vineger, which being mixed together make a quart and a quarter of a pint more, then take six ounces of gauls beaten into small pouder and sifted through a sive, put this pouder into a pot by it selfe, and poure halfe the water, wine and vineger into it, take likewise foure ounces of vietriall, and beat it into pouder, and put it also in a pot by it selfe, whereinto put a quarter of the wine, water, and vineger that remaineth, and to the other quarter, put foure ounces of gum Arabike beaten to pouder, that done, cover the three pots close, and let them stand three or foure daies together, stirring them every day three or foure times, on the first day set the pot with gaules on the fire, and when it begins to seeth, stir it about till it be throughly warme, then straine it through a cloath into another pot, and mixe it with the other two pots, stirring them well together, and being covered, then let it stand three daies, til thou meanest to use it, on the fourth day, when it is setled, poure it out, and it wil be good inke.

If there remaine any dregs behind, poure some raine water that hath stand long in a tub or vessell into it, for the older the water is, the better it is, and keepe that untill you make more inke, so it is better then clean water.

Sources:

The Insect Epiphany: How Our Six-Legged Allies Shape Human Culture, by Barrett Klein, October 2024

https://irongallink.org/iron-gall-ink-ink-of-kings-monks-and-poets.html

https://www.hiddelbrock.co.uk/post/oak-gall-wasps-and-other-galls

https://www.dayspringpens.com/blogs/the-jotted-line/what-ballpoint-pen-ink-made